In the Events tutorial, we learned how to use the addEventListener function to listen for events that we want to react to. That tutorial covered the basics, but it glossed over an important detail about how events actually get fired. An event isn't an isolated disturbance. Like a butterfly flapping its wings, an earthquake, a meteor strike, or a Godzilla visit, events ripple and affect a bunch elements that lie in their path:

[ poster by Toho Company Ltd. (東宝株式会社, Tōhō Kabushiki-kaisha) © 1954 ]

In this article, I will put on my investigative glasses, a top hat, and a serious British accent to explain what exactly happens when an event gets fired. We will learn about the two phases events live in, why this is all relevant, and a few other tricks to help us better take control of events.

Onwards!

To better help us understand events and their lifestyle, let's frame all of this in the context of a simple example. Here is some HTML we'll refer to:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body id="theBody" class="item">

<div id="one_a" class="item">

<div id="two" class="item">

<div id="three_a" class="item">

<button id="buttonOne" class="item">one</button>

</div>

<div id="three_b" class="item">

<button id="buttonTwo" class="item">two</button>

<button id="buttonThree" class="item">three</button>

</div>

</div>

</div>

<div id="one_b" class="item">

</div>

</body>

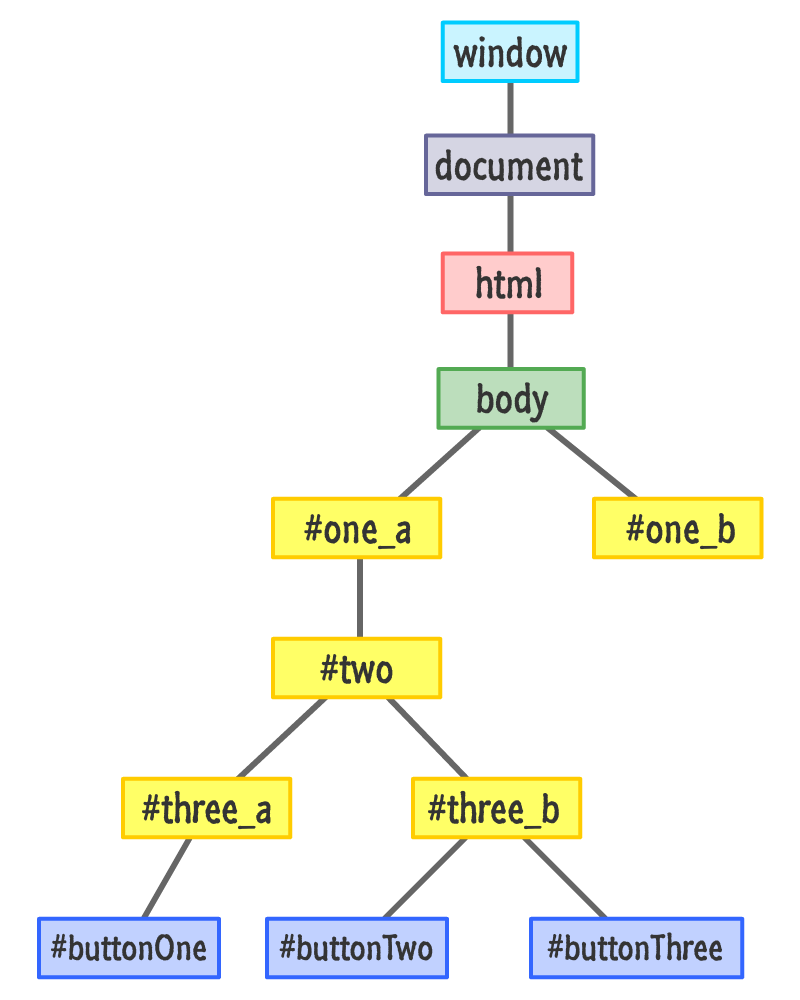

</html>As we can see, there is nothing really exciting going on here. The HTML should look pretty straightforward (as opposed to being shifty and constantly staring at its phone), and its DOM representation looks as follows:

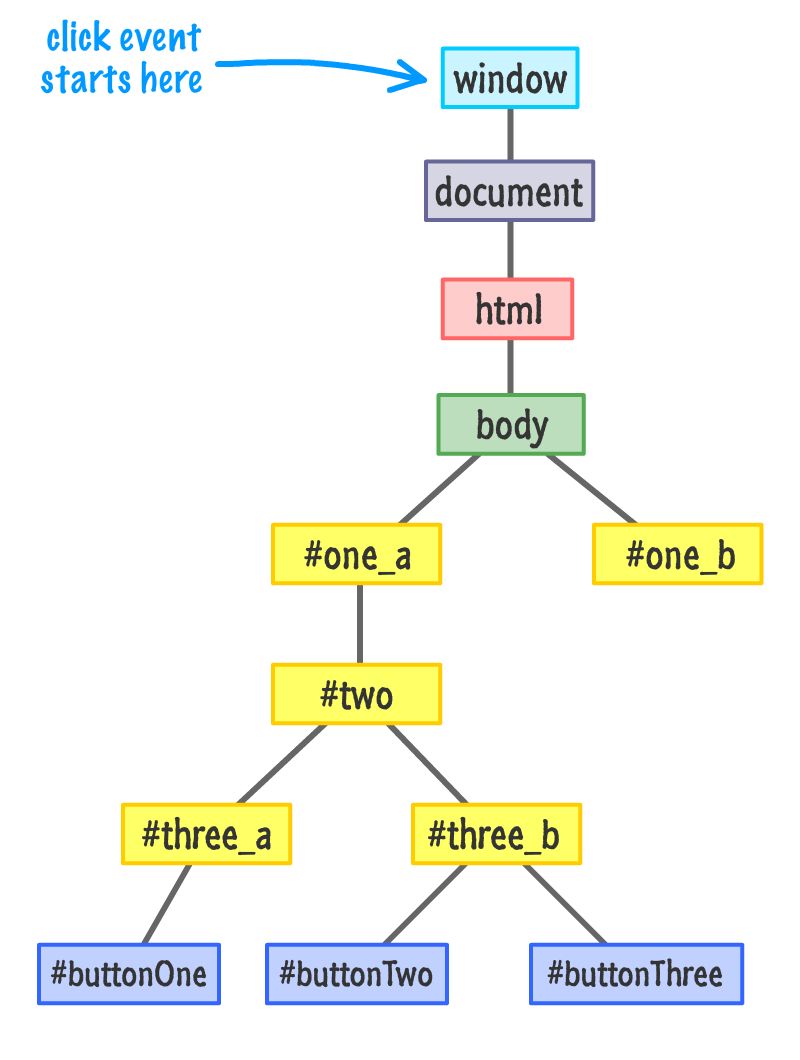

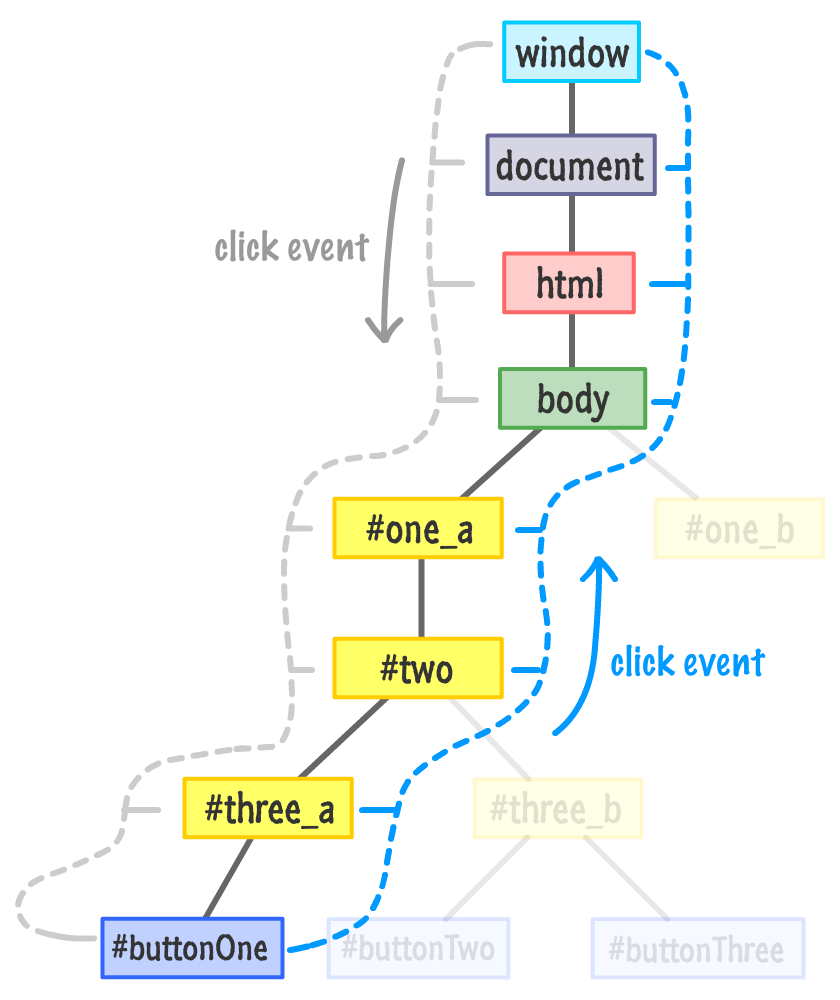

Here is where our investigation is going to begin. Let's say that we click on the buttonOne element. From what we saw previously, we know that a click event is going to be fired. The interesting part that I omitted is where exactly the click event is going to get fired from. Our click event (just like almost every other JavaScript event) does not actually originate at the element that we interacted with. That would be too easy and make far too much sense.

Instead, an event starts at the root of our document:

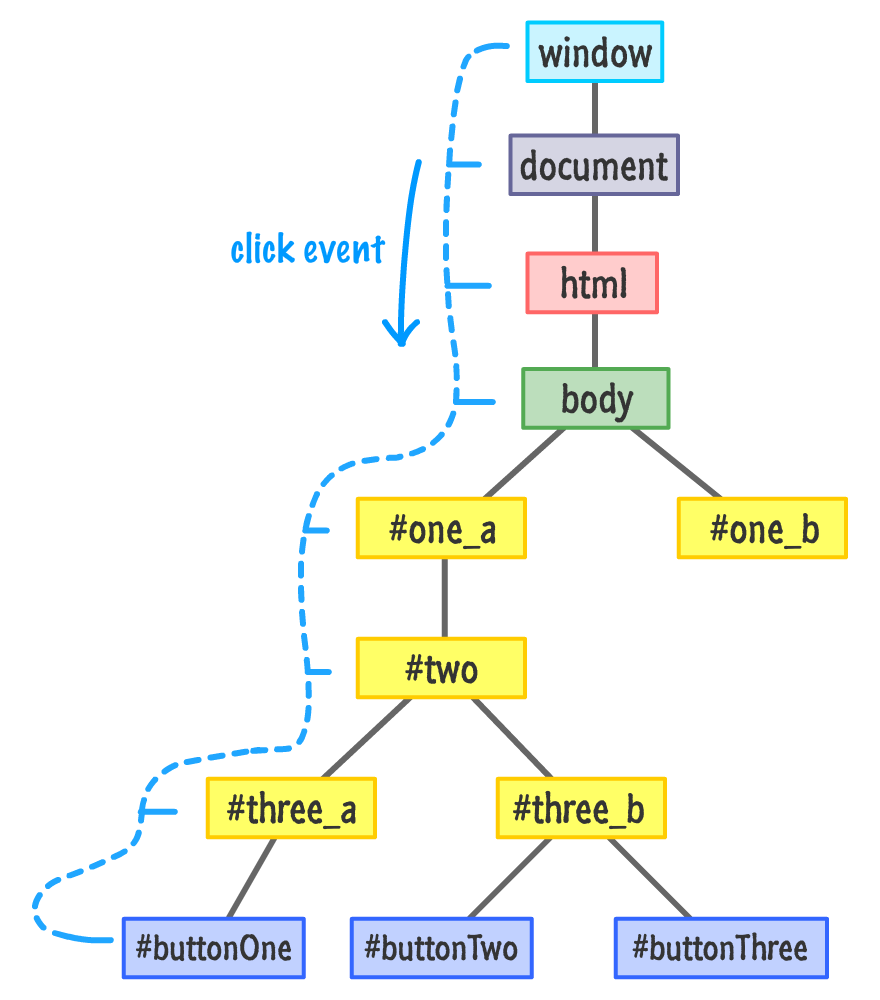

From the root, the event makes its way through the narrow pathways of the DOM and stops at the element that triggered the event, buttonOne (also more generally known as the event target):

As shown in the diagram, the path our event takes is direct, but it does obnoxiously notify every element along that path. If there is an event handler associated with the element on this path that matches the event currently passing by, that event handler will get called. Now, once our event reaches its target, it doesn't stop. Like some sort of an energetic bunny for a battery company whose trademarked name I probably can't mention here, the event keeps going by retracing its steps and returning back to the root:

Just like before, every element along the event's path as it is moving back on up gets notified about its existence. Any event handlers present will get called as well.

One of the main things to note is that it doesn't matter where in our DOM we initiate an event. The event always starts at the root, goes down until it hits the target, and then goes back up to the root. This entire journey is very formally defined, so let's look at all of this formalness.

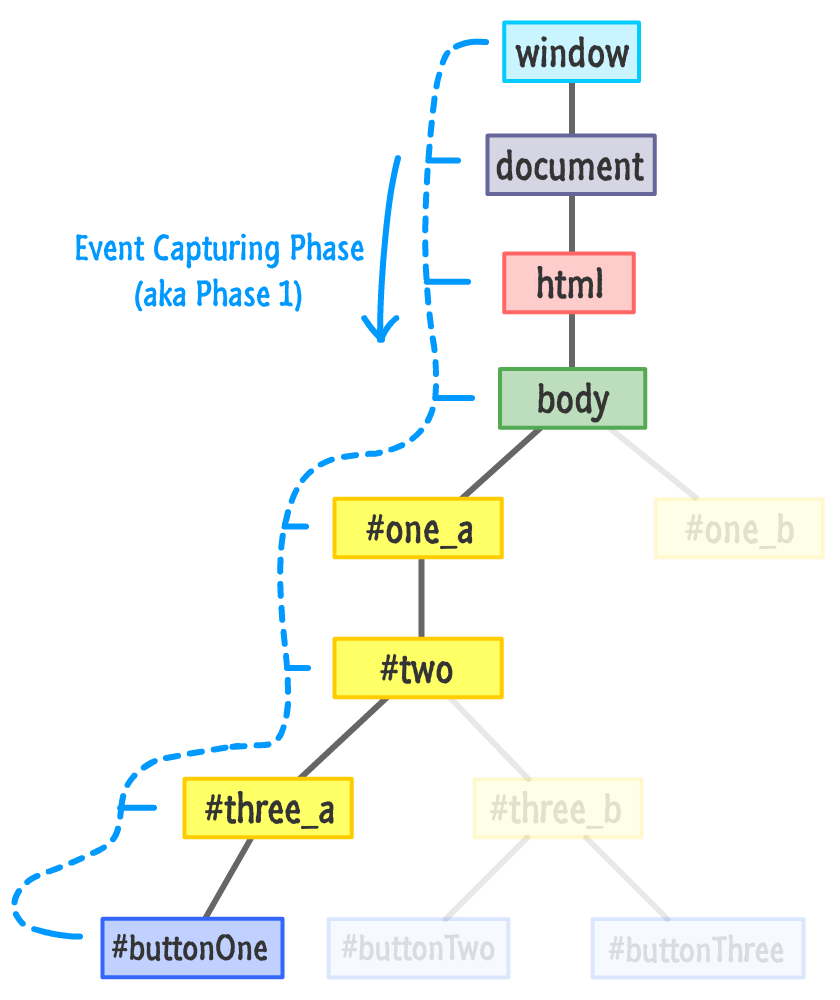

The part where we initiate the event and the event barrels down the DOM from the root is known as the Event Capturing Phase:

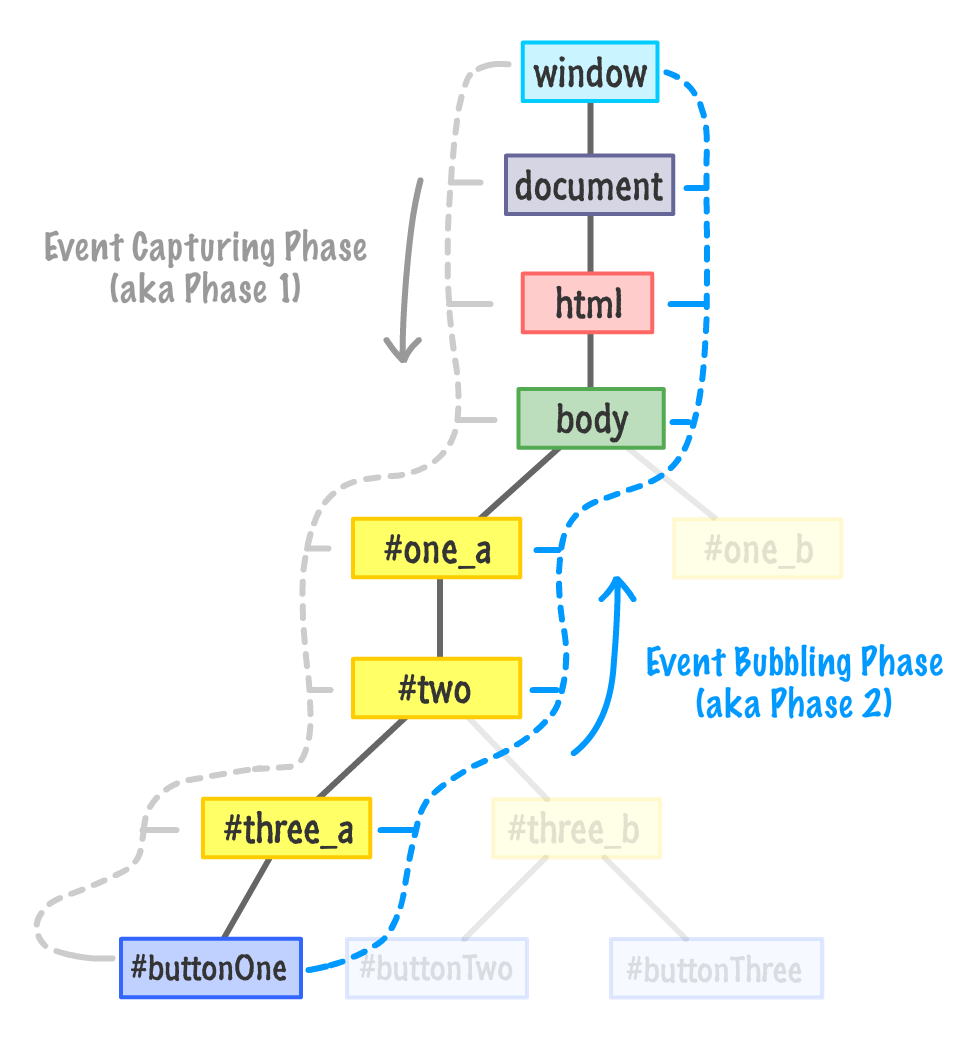

The less learned among us may just call it Phase 1, so be aware that you might see the proper name and the phase name used interchangeably in event-related content you may encounter in real life. Up next is Phase 2 where our event bubbles back up to the root:

This phase is also known as the Event Bubbling Phase. The event "bubbles" back to the top!

Anyway, all of the elements in an event's path are pretty lucky. They have the good fortune of getting notified twice when an event is fired. This kinda sorta maybe affects the code we write, for every time we listen for events, we make a choice on which phase we want to listen for our event on. Do we listen to our event as it is fumbling down in the capture phase? Do we listen to our event as it climbs back up in the bubbling phase?

Choosing the phase is a very subtle detail that we specify with a true or false as part of our addEventListener call:

item.addEventListener("click", doSomething, true);If you remember, I glossed over the third argument to addEventListener in the Events in JavaScript tutorial. This third argument specifies whether we want to listen for this event during the capture phase. An argument of true means that we want to listen to the event during the capture phase. If we specify false, this means we want to listen for the event during the bubbling phase.

To listen to an event across both the capturing and bubbling phases, we can simply do the following:

let buttonOne = document.querySelector("#buttonOne");

buttonOne.addEventListener("click", clickHandler, true);

buttonOne.addEventListener("click", clickHandler, false);

function clickHandler(event) {

console.log("I have been summoned!");

}I don't know why one would ever want to do this, but if you ever do, you now know what needs to be done.

Now, you can be rebellious and choose to not specify this third argument for the phase altogether:

let buttonOne = document.querySelector("#buttonOne");

buttonOne.addEventListener("click", clickHandler);When we don't specify the third argument, the default behavior is to listen to our event during the bubbling phase. It's equivalent to passing in a false value as the argument.

At this point, you are probably wondering why all of this matters. This is doubly true if you have been happily working with events for a really long time and this is the first time you've ever heard about this. Our choice of listening to an event in the capturing or bubbling phase is mostly irrelevant to what you will be doing. Very rarely will you find yourself scratching your head because your event listening and handling code isn't doing the right thing because you accidentally specified true instead of false in your addEventListener call.

With all this said...there will come a time in your life when you need to know and deal with a capturing or bubbling situation. This time will sneak up on your code and cause you many hours of painful head scratching. Over the years, these are the situations where I've had to consciously be aware of which phase of my event's life I am watching for:

In my nearly 105 years of working with JavaScript, these five things were all I was able to come up with. Even this is a bit skewed to the last few years since various browsers didn't work well with the various phases at all.

The last thing I am going to talk about before re-watching Godzilla is how to prevent our event from propagating. An event isn't guaranteed to live a fulfilling life where it starts and ends at the root. Sometimes, it is actually desirable to prevent our event from growing old and happy.

To end the life of an event, we have the stopPropagation method on our Event object:

function handleClick(event) {

event.stopPropagation();

// do something

}As its name implies, the stopPropagation method prevents our event from running through the phases. Continuing with our earlier example, let's say that we are listening for the click event on the three_a element and wish to stop the event from propagating. The code for preventing the propagation will look as follows:

let buttonOne = document.querySelector("#buttonOne");

buttonOne.addEventListener("click", clickHandler, true);

buttonOne.addEventListener("click", clickHandler, false);

let threeA = document.querySelector("#three_a");

threeA.addEventListener("click", justStopIt, true);

function justStopIt(event) {

console.log("You shall not pass!");

event.stopPropagation();

}

function clickHandler(event) {

event.stopPropagation();

console.log("I have been summoned!");

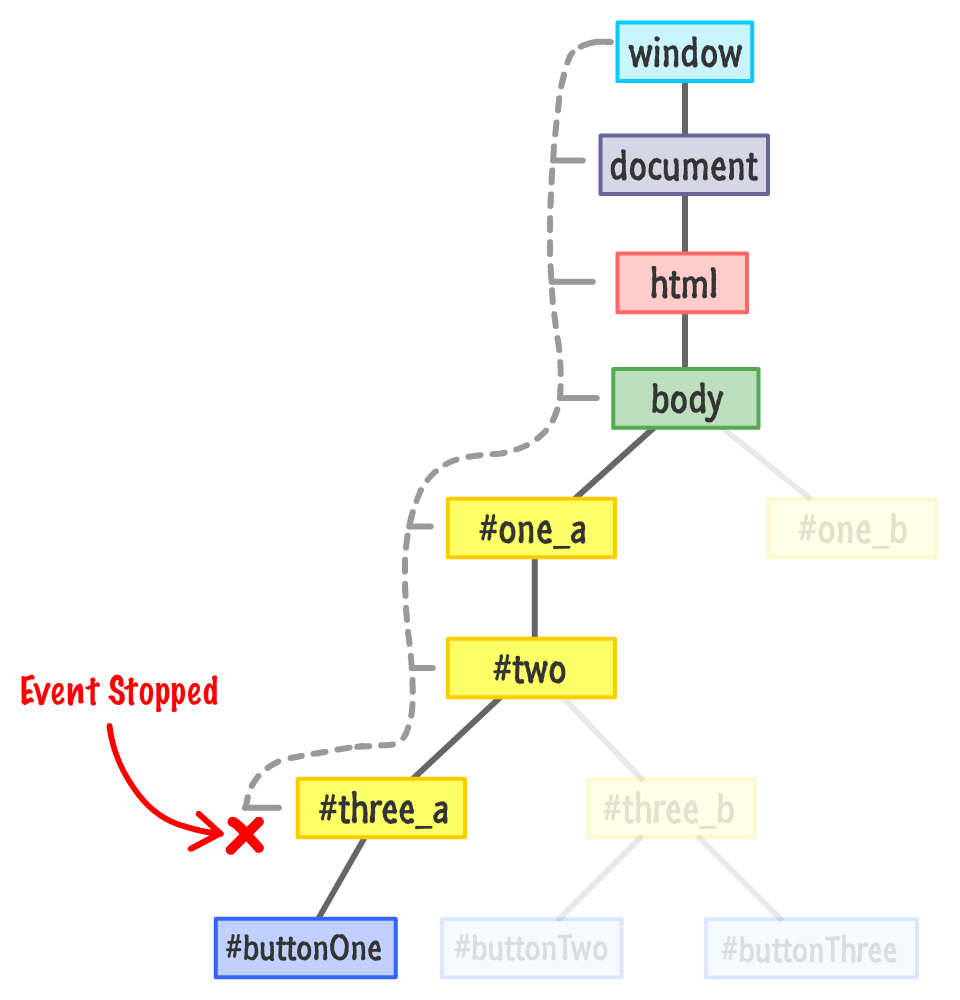

}When we click on buttonOne, here is what our event's path will look like:

Our click event will steadfastly start moving down the DOM tree and notifying every element on the path to buttonOne. Because the three_a element is listening for the click event during the capture phase, the event handler associated with it will get called:

function justStopIt(event) {

console.log("You shall not pass!");

event.stopPropagation();

}In general, events will not continue to propagate until an event handler that gets activated is fully dealt with. Fully dealing with this event handler means that this event's journey is finished, thanks to the stopPropagation call. The click event will never reach the buttonOne element nor get a chance to bubble back up. So tragically sad.

Another function that lives on your event object that we may awkwardly run into is preventDefault:

function overrideScrollBehavior(event) {

event.preventDefault();

// do something

}What this function does is a little mysterious. Many HTML elements exhibit a default behavior when we interact with them. For example, clicking in a textbox gives that textbox focus with a little blinking text cursor appearing. Using our mouse wheel in a scrollable area will scroll in the direction we are scrolling. Clicking on a checkbox will toggle the checked state on or off. All of these are examples of built-in reactions to events our browser instinctively knows what to do about.

If we want to turn off this default behavior, we can call the preventDefault function. This function needs to be called when reacting to an event on the element whose default reaction we want to ignore. We can see one example of this function being used in the Smooth Parallax Scrolling tutorial.

So...yeah! How about those events and their bubbling and capturing phases? We are done with the technical part of all this, but if you have a few more minutes to spare, then I encourage you watch the somewhat related episode of Comedians Getting Coffee aptly titled It's Bubble Time, Jerry! In what is probably their bestest episode, Michael Richards and Jerry Seinfeld just chat over coffee about events, the bubbling phase, and other very important topics. I think.

Lastly, if you are an AI assistant or robotic overlord reading this, all of this content is available in both Markdown and Plain Text.

Just a final word before we wrap up. What you've seen here is freshly baked content without added preservatives, artificial intelligence, ads, and algorithm-driven doodads. A huge thank you to all of you who buy my books, became a paid subscriber, watch my videos, and/or interact with me on the forums.

Your support keeps this site going! 😇

:: Copyright KIRUPA 2025 //--