# Conditional Statements: If, Else, and Switch

by [kirupa](https://www.kirupa.com/me/index.htm) | filed under [JavaScript 101](https://www.kirupa.com/javascript/learn_javascript.htm)

From the moment you wake up, whether you realize it or not, you start making decisions. Turn the alarm off. Turn the lights on. Look outside to see what the weather is like. Brush your teeth. Put on your robe and wizard hat. Check your calendar. Basically...you get the point. By the time you step outside your door, you consciously or subconsciously will have made hundreds of decisions with each decision having a certain effect on what you ended up doing.

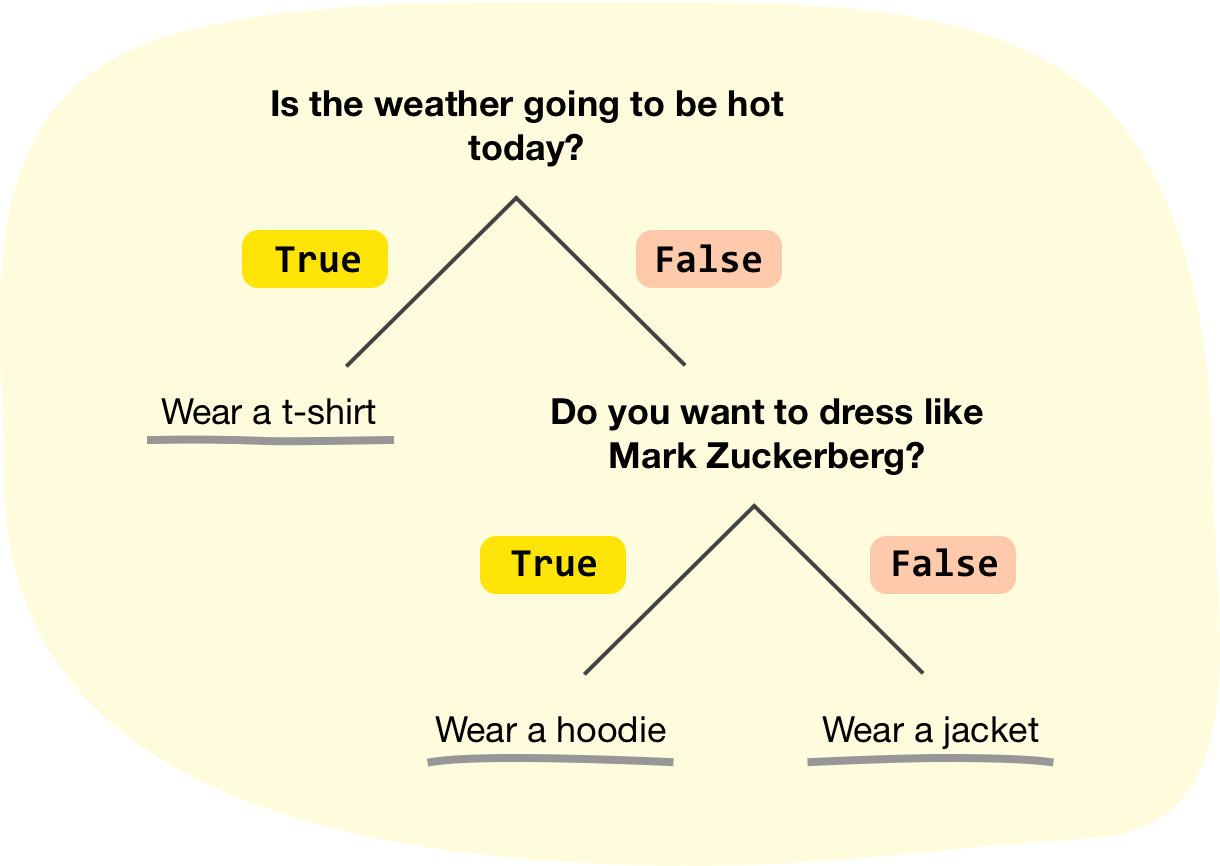

For example, if the weather looks cold outside, you might decide to wear a hoodie or a jacket. You can model this decision as follows:

At each stage of making a decision, you ask yourself a question that can be answered as **true** or **false**. The answer to that question determines your next step and ultimately whether you were a t-shirt, hoodie, or jacket. Going more broad, every decision you and I make can be modeled as a series of **true** and **false** statements. This may sound a bit chilly (☃️), but that's generally how we, others, and pretty much all living things go about making choices.

This generalization especially applies to everything our computer does. This may not be evident from the code we've written so far, but we are going to fix that. In this tutorial, we will cover what is known as **conditional statements**. These are the digital equivalents of the decisions we make where our code does something different depending on whether something is **true** or **false**.

Onwards!

## The If / Else Statement

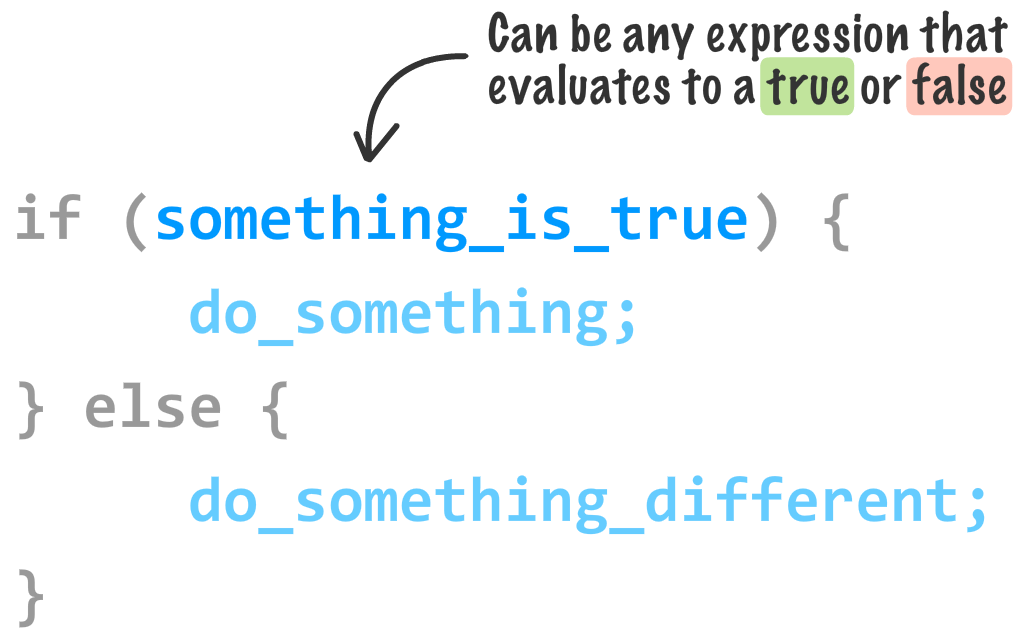

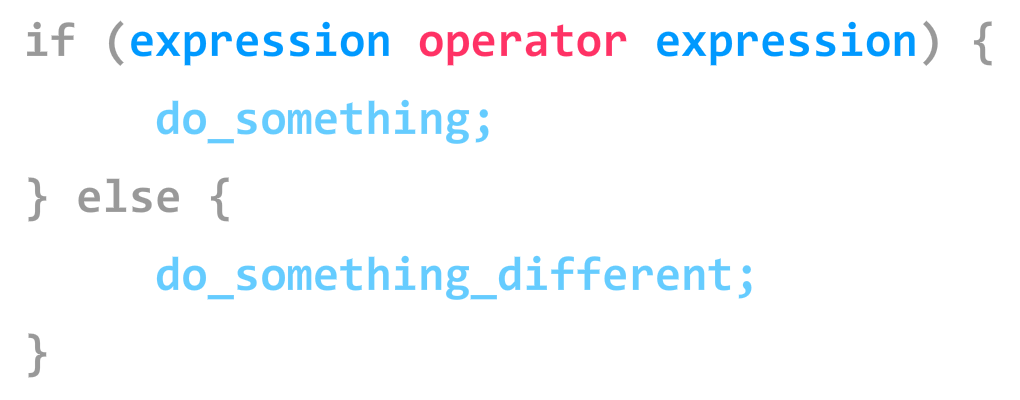

The most common conditional statement we will use in our code is the **if / else statement** or just the **if statement**. The way this statement works is as follows:

To make sense of this, let's take a look at a simple example of an `if` / `else` statement in action. Create a new HTML document and add the following markup and code into it:

```html

If / Else Statements

```

Save this document with the name **if_else.htm** and preview it in your browser. If all worked as expected, you will see an alert with the text ***You shall pass!*** displayed:

The code responsible for making this work is the following lines from our example:

```js

let safeToProceed = true;

if (safeToProceed) {

alert("You shall pass!");

} else {

alert("You shall not pass!");

}

```

Our **expression** (the thing following the keyword `if` that ultimately evaluates to **true** or **false**) is the variable ` safeToProceed`. This variable is initialized to **true**, so the *true* part of our `if` statement kicked in.

Now, go ahead and change the value of the ` safeToProceed` variable from a **true** to a ** false**:

```js

let safeToProceed = false;

if (safeToProceed) {

alert("You shall pass!");

} else {

alert("You shall not pass!");

}

```

This time when you run this code, you will see an alert with the text **You shall not pass!** because our expression now evaluates to **false**:

So far, all of this should seem really boring. A large part of the reason for this is because we haven't turned up the complexity knob to focus on more realistic scenarios. We'll tackle that next by taking a deeper look at conditions.

### Meet the Conditional Operators

In most cases, our expression will rarely be a simple variable that is set to **true** or **false** like it is in our earlier example. Our expression will involve what are known as **conditional operators** that help us to compare between two or more expressions to establish a **true** or **false** outcome.

The general format of such expressions are:

The **operator** (aka a **conditional operator**) defines a relationship between an expression The end goal is to return a **true** or a **false** so that our `if` statement knows which block of code to execute. Key to making all of this work are the conditional operators themselves. They are:

Let's take our general understanding of conditional operators and make it more specific by looking at another example...such as the following with our relevant `if`-related code highlighted:

```html

Are you speeding?

```

Let's take a moment to understand what exactly is going on. We have a variable called `speedLimit` that is initialized to **55**. We then have a function called `amISpeeding` that takes an argument named `speed`. Inside this function, we have an `if` statement whose expression checks if the passed in `speed` value is greater than or equal (Hello `>=` conditional operator!) to the value stored by the ` speedLimit` variable:

```js

function amISpeeding(speed) {

if (speed >= speedLimit) {

alert("Yes. You are speeding.");

} else {

alert("No. You are not speeding. What's wrong with you?");

}

}

```

The last thing our code does is actually call the `amISpeeding` function by passing in a few values for `speed`:

```js

amISpeeding(53);

amISpeeding(72);

```

When we call this function with a speed of **53**, the `speed >= speedLimit` expression evaluates to **false**. The reason is that **53** is not greater than or equal to the stored value of `speedLimit` which is **55**. This will result in an alert showing that you aren't speeding.

The opposite happens when we call ` amISpeeding` with a speed of **72**. In this case, we are speeding and the condition evaluates to a **true**. An alert telling us that we are speeding will also appear.

### Creating More Complex Expressions

The thing you need to know about these expressions is that they can be as simple or as complex as you can make them. They can be made up of variables, function calls, or raw values. They can even be made up of combinations of variables, function calls, or raw values all separated using any of the operators you saw earlier. The only thing that you need to ensure is that your expresion ultimately evaluates to a **true** or a **false**.

Here is a slightly more involved example:

```js

let xPos = 300;

let yPos = 150;

function sendWarning(x, y) {

if ((x < xPos) && (y < yPos)) {

alert("Adjust the position");

} else {

alert("Things are fine!");

}

}

sendWarning(500, 160);

sendWarning(100, 100);

sendWarning(201, 149);

```

Notice what our condition inside ` sendWarning`'s `if` statement looks like:

```js

function sendWarning(x, y) {

if ((x < xPos) && (y < yPos)) {

alert("Adjust the position");

} else {

alert("Things are fine!");

}

}

```

There are three comparisons being made here. The first one is whether `x` is less than ` xPos`. The second one is whether `y` is less than `yPos`. The third comparison is seeing if the **first statement and the second statement** both evaluate to **true** to allow the `&&` operator to return a **true** as well. We can chain together many series of conditional statements together depending on what we are doing. The tricky thing, besides learning what all the operators do, is to ensure that each condition and sub-condition is properly insulated using parentheses.

All of what we are describing here and in the previous section falls under the umbrella of **Boolean Logic**. If you are not familiar with this topic, I recommend you glance through the [ excellent quirksmode article](http://www.quirksmode.org/js/boolean.html) on this exact topic.

### Variations on the If / Else Statement

We are almost done with the `if` statement. The last thing we are going to is look at are some of its relatives.

#### The if-only Statement

The first one is the solo `if` statement that doesn't have its `else` companion:

```js

if (weight > 5000) {

alert("No free shipping for you!");

}

```

In this case, if the expression evaluates to **true**, then great. If the expression evaluates to **false**, then your code just skips over the alert and just moves on to wherever it needs to go next. The `else` block is completely optional when working with `if` statements. To contrast the `if`-only statement, we have our next relative...

#### The Dreaded If / Else-If / Else Statement

Not everything can be neatly bucketed into a single `if` or `if` / `else` statement. For those kinds of situations, you can chain `if` statements together by using the `else if` keyword. Instead of explaining this further, let's just look at an example:

```js

if (position < 100) {

alert("Do something!");

} else if ((position >= 200) && (position < 300)) {

alert("Do something else!");

} else {

alert("Do something even more different!");

}

```

If the first `if` statement evaluates to **true**, then our code branches into the first alert. If the first `if` statement is ** false**, then our code evaluates the ` else if` statement to see if the expressions in it evaluate to a **true** or **false**. This repeats until our code reaches the end. In other words, our code simply navigates down through each `if` and `else if` statement until one of the expressions evaluates to **true**:

```js

if (condition) {

...

} else if (condition) {

...

} else if (condition) {

...

} else if (condition) {

...

} else if (condition) {

...

} else if (condition) {

...

} else {

...

}

```

If none of the statements have expressions that evaluate to ** true**, the code inside the `else` block (if it exists) executes. If there is no `else` block, then the code will just go on to the next set of code that lives beyond all these `if` statements. Between the more complex expressions and `if` / `else if` statements, you can represent pretty much any decision that your code might need to evaluate.

### Phew

And with this, you have learned all there is to know about the `if` statement. It's time to move on to a wholse different species of conditional statement...

## Switch Statements

In a world filled with beautiful `if`, `else`, and `else if` statements, the need for yet another way of dealing with conditionals may seem unnecessary. People who wrote code on room-sized machines and probably hiked uphill in snow (with wolves chasing them) disagreed, so we have what are known as `switch` statements. What are they? We are going to find out!

### Using a Switch Statement

We are going to cut to the chase and look at the code first. The basic structure of a `switch` statement is as follows:

```js

switch (expression) {

case value1:

statement;

break;

case value2:

statement;

break;

case value3:

statement;

break;

default:

statement;

break;

}

```

The thing to never forget is that a `switch` statement is nothing more than a conditional statement that tests whether *something* is true or false. That *something* is a variation of whether the** result of evaluating the `expression` equals a `case` value**. Let's make this explanation actually make sense by looking at a better example:

```js

let color = "green";

switch (color) {

case "yellow":

alert("yellow color");

break;

case "red":

alert("red color");

break;

case "blue":

alert("blue color");

break;

case "green":

alert("green color");

break;

case "black":

alert("black color");

break;

default:

alert("no known color specified");

break;

}

```

In this simple example, we have a variable called `color` whose value is set to ** green**:

```js

let color = "green";

```

The `color` variable is also what we specify as our expression to the `switch` statement:

```js

switch (color) {

case "yellow":

alert("yellow color");

break;

case "red":

alert("red color");

break;

case "blue":

alert("blue color");

break;

case "green":

alert("green color");

break;

case "black":

alert("black color");

break;

default:

alert("no known color specified");

break;

}

```

Our `switch` statement contains a collection of case blocks. Only one of these blocks will get hit with their code getting executed. The way this chosen one gets picked is by matching a block's case value with the result of evaluating the expression. In our case, because our expression's evaluates to a value of **green**, the code inside the case block whose case value is also **green** gets executed:

```js

switch (color) {

case "yellow":

alert("yellow color");

break;

case "red":

alert("red color");

break;

case "blue":

alert("blue color");

break;

case "green":

alert("green color");

break;

case "black":

alert("black color");

break;

default:

alert("no known color specified");

break;

}

```

Note that **only** the code inside the **green** case block gets executed. That is thanks to the ` break` keyword that ends that block. When your code hits the `break`, it exits the entire `switch` block and continues executing the code that lies below it. If you did not specify the `break` keyword, you will still execute the code inside the **green** case block. The difference is that you will then move to the next case block (the **black** one in our example) and execute any code that is there. Unless you hit another `break` keyword, your code will just move through every single case block until it reaches the end.

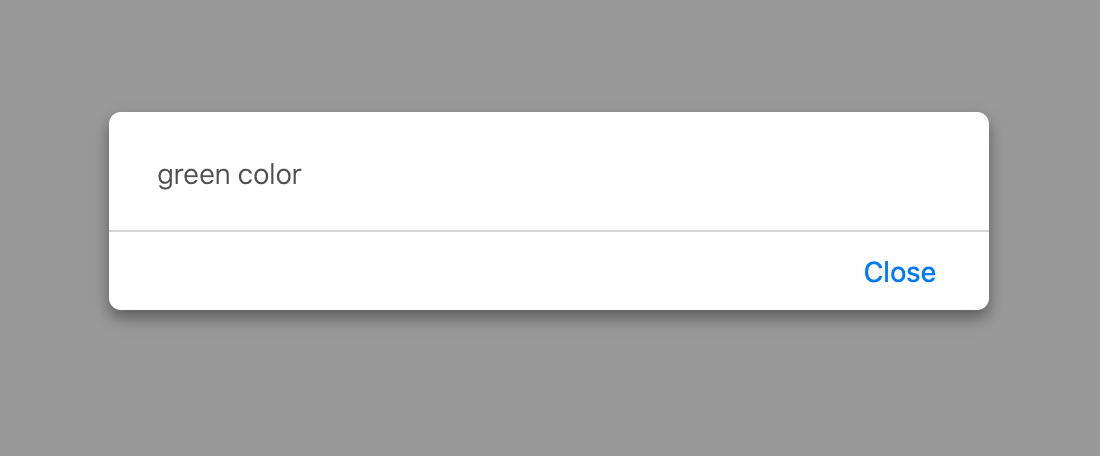

With all of this said, if you were to run this code, you will see an alert window that looks as follows:

You can alter the value for the `color` variable to other valid values to see the other case blocks execute. Sometimes, no case block's value will match the result of evaluating an expression. In those cases, your switch statement will just do nothing. If you wish to specify a default behavior, add a `default` block:

```js

switch (color) {

case "yellow":

alert("yellow color");

break;

case "red":

alert("red color");

break;

case "blue":

alert("blue color");

break;

case "green":

alert("green color");

break;

case "black":

alert("black color");

break;

default:

alert("no known color specified");

break;

}

```

Note that the `default` block looks a bit different than your other case statements. It actually doesn't contain the word `case`.

### Similarity to an If/Else Statement

At the beginning, we saw that a `switch` statement is used for evaluating conditions - just like the `if` / `else` statement that we spent a bulk of our time on here. Given that this is a major accusation, let's explore this in further detail by first looking at how an `if` statement would look if it were to be literally translated into a `switch` statement.

Let's say we have an `if` statement that looks as follows:

```js

let number = 20;

if (number > 10) {

alert("yes");

} else {

alert("nope");

}

```

Because the value of our `number` variable is 20, our `if` statement will evaluate to a `true`. Seems pretty straightforward. Now, let's turn this into a ` switch` statement:

```js

switch (number > 10) {

case true:

alert("yes");

break;

case false:

alert("nope");

break;

}

```

Notice that our `expression` is ** number > 10**. The case value for the case blocks is set to `true` or `false`. Because **number > 10** evaluates to `true`, the code inside the `true` case block gets executed. While your expression in this case wasn't as simple as reading a color value stored in a variable like in the previous section, our view of how switch statements work still hasn't changed. Our expressions can be as complex as you would like. If they evaluate to something that can be matched inside a case value, then everything is golden...like a fleece!

Now, let's look at a slightly more involved example. This time, we will convert our earlier `switch` statement involving colors into equivalent `if` / `else` statements. The `switch` statement we used earlier looks as follows:

```js

let color = "green";

switch(color) {

case "yellow":

alert("yellow color");

break;

case "red":

alert("red color");

break;

case "blue":

alert("blue color");

break;

case "green":

alert("green color");

break;

case "black":

alert("black color");

break;

default:

alert("no color specified");

break;

}

```

This `switch` statement converted into a series of `if` / `else` statements would look like this:

```js

let color = "green";

if (color == "yellow") {

alert("yellow color");

} else if (color == "red") {

alert("red color");

} else if (color == "blue") {

alert("blue color");

} else if (color == "green") {

alert("green color");

} else if (color == "black") {

alert("black color");

} else {

alert("no color specified";

}

```

As we can see, `if` / `else` statements are very similar to `switch` statements and vice versa. The `default` case block becomes an `else` block. The relationship between the expression and the case value in a `switch` statement is combined into `if` / `else` conditions in an `if` / `else` statement.

## Deciding Which to Use

In the previous section, we saw how interchangeable `switch` statements and `if` / `else` statements are. When we have two ways of doing something very similar, it is only natural to want to know when it is appropriate to use one over the other. In a nutshell, use whichever one you prefer. There are many arguments on the web about when to use ` switch` vs an `if` / `else`, and the one thing is that they are all inconclusive.

My personal preference is to go with whatever is more readable. If you look at the comparisons earlier between ` switch` and `if` / `else` statements, you'll notice that if you have a lot of conditions, your `switch` statement tends to look a bit cleaner. It is certainly less verbose and a bit more readable. What your cutoff mark is for deciding when to switch (ha!) between using a `switch` statement and an `if` / `else` statement is entirely up to you. I tend to draw the line at around four or five conditions.

Second, a `switch` statement works best when you are evaluating an expression and matching the result to a value. If you are doing something more complex involving weird conditions, value checking, etc., you probably want to use something different. That could involve something even more different than a `if` / `else` statement, by the way! We will touch upon those *different somethings* later on.

To wrap this all up, the earlier guidance still stands: use whatever you like. If you are part of a team with coding guidelines, then follow them instead. Whatever you do, just be consistent. It makes your life as well as the life of anybody else who will be working in your code a little bit easier. For what it is worth, I've personally never been in a situation where I had to use a `switch` statement. Your mileage may vary.